Payment in the US Healthcare has traditionally been a fee for service model. If I go to the doctor, the doctor receives a certain amount of money. The more that I go to the doctor and the more procedures are done to me,, the more money the doctor receives. If I’m healthy and never go to the doctor, the doctor makes no money.

This model makes intuitive sense, but it also provides some weird incentives to the doctors. If the doctor doesn’t properly manage a condition and the condition worsens, ironically the doctor generally makes more money. There is very little financial incentive for them to provide a certain level of quality (and usually an incentive not to, such as only scheduling 5 minutes with a patient).

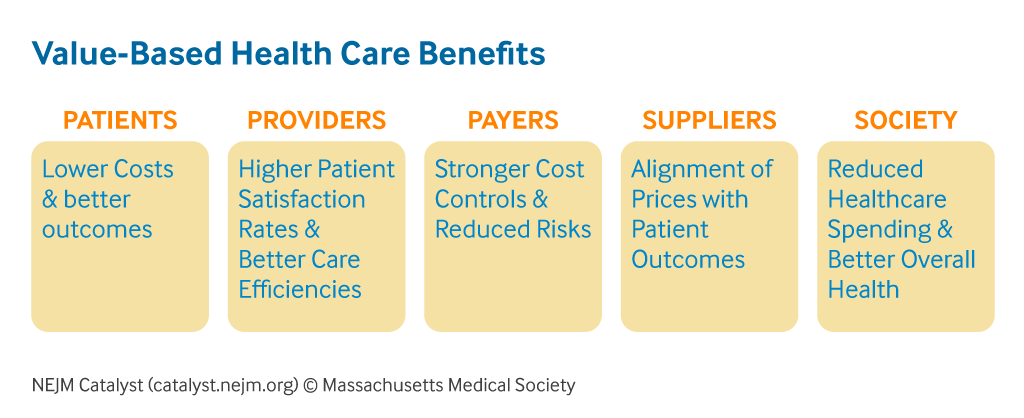

To be clear – I’m not accusing doctors of purposely gaming the system for financial gains (although a few do), but the concept of value based healthcare is to tie quality of care to the payment model. If all of a doctor’s patients are well managed (and hence rarely see the doctor), the doctor should be rewarded for this – not punished.

So value based healthcare is a new type of contract between the insurance company and the provider, which can be a small practice, or a larger entity like a hospital system( e.g. in the Seattle area, examples would include Swedish Medical, UW Medical or Evergreen Healthcare) that determines how the provider gets paid.

Different types/levels of Value Based Healthcare

This is a gross simplification and I’m purposely leaving out episodes of care and bundled payments (partly because I didn’t work on those as closely and partly because they get more complicated).

There are three levels of value based healthcare:

1. Quality Incentive

This is the lowest level of value based healthcare, and essentially means that the doctor collects their normal fee for service, but also gets a bonus if they meet some quality targets.

2. Shared savings

The predicted expense for the upcoming year is calculated for a provider, and if the provider is able to spend less money than the predicted target, the provider gets to keep some of that savings.

Shared savings programs always have a quality component as well. For example, if you provide no real benefit to your patients you will probably save a lot of money, but your quality assessment will drop too low for you to be paid.

3. Capitation.

The risk factor for each patient is determined and the doctor receives a certain amount of money each month for managing that patient’s health. Hence, the practice gets paid for every patient under their care every month (regardless how often the patient sees the doctor). If the patient is healthy and rarely sees the doctor, the risk score is low (so the payment is lower). If the patient is very sick, the risk score is higher (and the payment is higher).

The capitation models usually quality into account.

How is quality determined?

The program defines a set of metrics used to measure quality, and these metric sets are usually different for pediatrics, adults, and senior patients.

Often these metrics are defined by the NCQA and are known as HEDIS measures. For example, HEDIS measure “COL-E” evaluates the percentage of members aged 45-75 who receive appropriate screening for colorectal cancer. For each measure, a patient passes the measure, fails the measure, is not applicable to the measure.

Insurance companies can also create their own measures or they can modify an existing HEDIS measure (e.g. change the age range to which it applies, etc.).

The program also defines thresholds and scoring systems by which a provider is graded against these measures, which also takes into account the provider’s patient population. For example, if a provider does not have enough female patients to properly score a measure based on mammogram screening, the weighting of the measures for which they do qualify are re-weighted accordingly.

Pros of Value Based Healthcare

The pros of value based healthcare are:

- It encourages preventative care over reactive care:

- If a patient hasn’t been screened for something important (e.g. physical, mammogram, colorectal cancer, etc.) in a while, they are much more likely to get a phone call from the doctor’s office to schedule an appointment.

- If you have a procedure done, you may be more likely to get follow up phone calls to see how you are doing.

- As preventive care is almost always cheaper, it can reduce healthcare costs.

- This can lead to a healthier population.

- Practices are paid based on outcomes rather than simple volume. A practice that excels at healthy patient outcomes can be rewarded over one that is not.

Cons of Value Based Healthcare

The cons of value based healthcare are:

- It’s difficult to understand exactly how the payments are calculated and why, whereas the fee for service model is easy to understand (e.g. more visits = more money).

- Providers already do not trust the insurance companies to pay them fairly, so adding a complicated algorithm in the middle does nothing to improve that trust.

- It can slow down payment to providers. Bonuses are usually paid at the end of the program year, but since it takes a while for claims to clear, the payments are normally made at least six months after the program year has ended.

- Current value based programs vary too wildly. Practices see patients from many insurance companies, so the providers will contract with many different value based programs (which can all be different).

- For example, if we learned that mammogram screening was very low in a certain region, all programs could add mammogram screening to their program and theoretically that would lead doctors to encourage more screening.

- But if there is not much overlap between the measures used by different programs, then a practice has no real areas of focus.

- Some states are addressing this by defining value based programs at the state level that are then implemented by the different insurance companies.

Pingback: My Career – Part 24: Nuna – Talking Smac

Pingback: My Career – Part 23: Joining Nuna – Talking Smac